- UPSC LABS

- February 26, 2025

- 6:35 pm

- Ratings: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Buddhism and Jainism

The sixth century BCE in India was a period of profound intellectual and spiritual ferment. Amidst the dominance of Vedic rituals and the caste system, two heterodox traditions—Buddhism and Jainism—emerged as revolutionary movements. Founded by Gautama Buddha and Mahavira, respectively, these religions challenged orthodox Brahmanical practices, emphasizing ethical living, renunciation, and liberation. Their teachings reshaped India’s spiritual landscape and left an indelible mark on its art, culture, and society. This article explores the origins, philosophies, historical trajectories, and enduring legacies of Buddhism and Jainism, offering critical insights for UPSC aspirants.

The emergence of Buddhism and Jainism during this period was not an isolated phenomenon but a response to the socio-religious conditions of the time. The Vedic religion, with its emphasis on rituals and sacrifices, had become increasingly rigid and exclusionary. The caste system, which placed Brahmins at the top of the social hierarchy, created widespread discontent among the lower castes and non-Brahmin communities. Urbanization and the rise of new economic classes, such as merchants and traders, also contributed to the demand for more accessible and egalitarian spiritual paths. In this context, Buddhism and Jainism arose, offering alternative paths to salvation that were open to all, regardless of caste or social status.

Table of Contents

Buddhism: Origins and Core Teachings

Buddhism originated in the 6th century BCE with Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha (the Enlightened One). Born in Lumbini (modern Nepal) to the Shakya clan, Gautama’s encounter with human suffering prompted his renunciation of princely life. After years of asceticism and meditation, he attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya.

The Buddha’s teachings revolve around the Four Noble Truths:

Dukkha (Suffering): Life is inherently marked by suffering.

Samudaya (Cause): Suffering arises from desire (tanha).

Nirodha (Cessation): Suffering can end by eliminating desire.

Magga (Path): The Eightfold Path leads to liberation.

The Eightfold Path comprises the right view, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. Together, these principles form the Middle Way, rejecting both extreme asceticism and indulgence.

The Buddha’s teachings were not merely philosophical but also deeply practical. He emphasized the importance of personal experience and critical inquiry, urging his followers to test his teachings through their practice. This empirical approach set Buddhism apart from other religious traditions of the time, which often relied on scriptural authority and ritualistic practices. The Buddha’s emphasis on mindfulness and meditation as tools for self-transformation also made his teachings accessible to people from all walks of life.

Key Concepts and Sects

Buddhism’s philosophical framework includes Anatta (no permanent soul), Anicca (impermanence), and Karma (moral causality). The concept of Anatta challenges the notion of a permanent, unchanging self, asserting that what we perceive as the self is merely a collection of impermanent aggregates. Anicca underscores the transient nature of all phenomena, while Karma emphasizes the moral consequences of one’s actions.

The Sangha (monastic community) became central to preserving and propagating the Buddha’s teachings. Monks and nuns, who renounced worldly life to dedicate themselves to spiritual practice, played a crucial role in spreading Buddhism across India and beyond. The Sangha also served as a model of communal living, based on principles of equality, mutual respect, and ethical conduct.

Over time, Buddhism split into major sects:

Theravada (School of the Elders): Focuses on the Pali Canon and the Buddha’s original teachings. Theravada Buddhism, which is predominant in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, emphasizes individual liberation through personal effort and adherence to monastic discipline.

Mahayana (Great Vehicle): Emphasizes compassion and the ideal of the Bodhisattva (one who delays enlightenment to help others). Mahayana Buddhism, which spread to East Asia, introduced new scriptures and practices, such as the veneration of celestial Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Vajrayana (Diamond Vehicle): Incorporates esoteric rituals, prominent in Tibet. Vajrayana Buddhism, also known as Tantric Buddhism, emphasizes the use of mantras, mandalas, and other ritual practices to achieve enlightenment in a single lifetime.

Spread and Decline in India

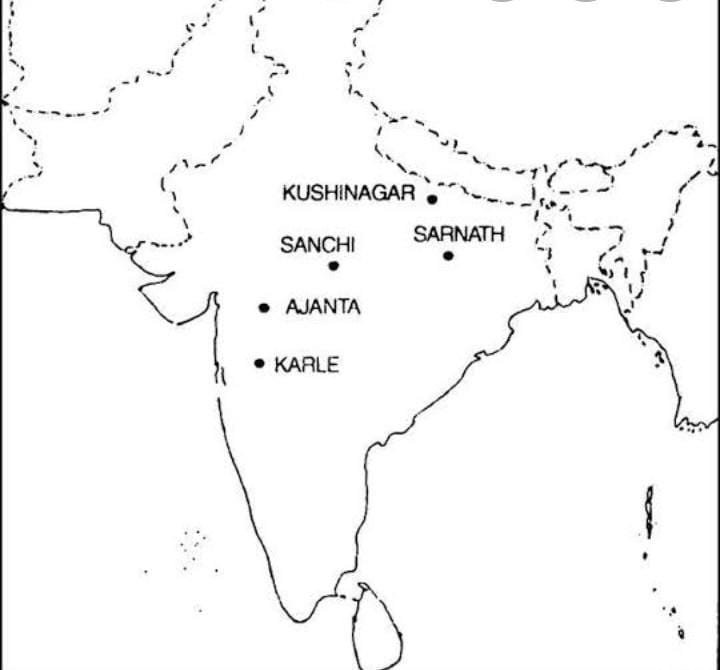

Buddhism’s expansion was catalyzed by Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BCE), who adopted it after the Kalinga War. Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism marked a turning point in the religion’s history. He not only promoted Buddhist teachings through his edict but also sent missionaries to distant regions, including Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and the Hellenistic world. Ashoka’s patronage of stupas, such as those at Sanchi and Bharhut, also contributed to the spread of Buddhist art and architecture.

The Fourth Buddhist Council under Kanishka (1st century CE) formalized Mahayana doctrines and led to the compilation of new scriptures. This period also saw the flourishing of Buddhist art and culture, particularly in the Gandhara and Mathura schools, which produced some of the earliest representations of the Buddha in human form.

However, by the 12th century CE, Buddhism declined in India due to the revival of Hinduism, Brahmanical assimilation, and Islamic invasions. The Bhakti movement, which emphasized devotion to personal deities, attracted many followers away from Buddhism. The destruction of monastic centers, such as Nalanda and Vikramashila, by invading armies further weakened the religion’s institutional base. Monastic isolation and the loss of royal patronage also contributed to Buddhism’s waning influence in its land of origin.

Jainism: Origins and Core Teachings

Jainism, contemporaneous with Buddhism, traces its roots to ancient Tirthankaras (ford-makers). The 24th Tirthankara, Vardhamana Mahavira (599–527 BCE), is regarded as its historical founder. Born in Vaishali (Bihar), Mahavira renounced worldly life at 30, achieving Kevala Jnana (omniscience) after 12 years of austerity.

Jain philosophy rests on three principles:

Ahimsa (Non-violence): Strict adherence to non-harm towards all life forms.

Anekantavada (Non-absolutism): Reality is multifaceted, advocating intellectual humility.

Aparigraha (Non-possessiveness): Detachment from material possessions.

The Five Mahavratas (vows)—ahimsa, satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity), and aparigraha—guide monastic life. Lay Jains follow diluted vows termed Anuvratas.

Jainism’s emphasis on Ahimsa extends beyond physical non-violence to include mental and verbal non-violence. This principle has had a profound impact on Indian culture, influencing dietary practices, environmental ethics, and social reform movements. Anekantavada, the doctrine of non-absolutism, encourages tolerance and respect for diverse perspectives, making Jainism a uniquely pluralistic tradition.

Sects and Practices

Jainism split into two major sects:

Digambara (Sky-clad): Monks renounce clothing, believing in complete detachment. Digambara Jainism, which is predominant in southern India, holds that women cannot achieve liberation without being reborn as men.

Svetambara (White-clad): Monks wear white robes, allowing women to attain liberation. Svetambara Jainism, which is more common in western India, has a more inclusive approach to gender and spiritual practice.

Jain rituals emphasize Sallekhana (ritual fasting unto death), meditation, and veneration of Tirthankaras. The religion’s emphasis on Syadvada (theory of conditioned predication) fosters tolerance by acknowledging partial truths. Jain temples, known for their intricate architecture and iconography, serve as centers of worship and community life.

Spread and Survival in India

Unlike Buddhism, Jainism remained confined to India, finding patronage under rulers like Chandragupta Maurya and Kharavela. The merchant community (Vaishyas) played a pivotal role in sustaining Jain practices through donations and temple construction. Despite regional fluctuations, Jainism endured due to its strong community networks and adaptability.

Jainism’s survival can also be attributed to its emphasis on lay participation. While monasticism remains central to Jain practice, lay Jains play an active role in supporting the monastic community and preserving religious traditions. This symbiotic relationship between monks and lay followers has ensured the continuity of Jainism over the centuries.

Comparative Analysis: Buddhism and Jainism

Similarities:

Both rejected Vedic authority, caste hierarchy, and ritual sacrifices.

They propagated asceticism and renunciation as paths to liberation.

Emphasis on ethics over metaphysical speculation.

Differences:

Concept of Soul: Jainism upholds Jiva (eternal soul), while Buddhism denies a permanent self (Anatta).

Approach to Ahimsa: Jainism’s absolutist non-violence contrasts with Buddhism’s contextual approach.

Ascetic Practices: Jain monks practice extreme austerity (e.g., fasting, nudity), whereas Buddhists follow the Middle Way.

Despite their differences, Buddhism and Jainism share a common commitment to ethical living and spiritual liberation. Both traditions have made significant contributions to Indian philosophy, art, and culture, and continue to inspire millions of followers worldwide.

Contributions to Indian Culture

Buddhism:

Education: Monasteries like Nalanda and Vikramashila became global learning centers, attracting scholars from across Asia. These institutions not only preserved Buddhist teachings but also advanced knowledge in fields such as medicine, astronomy, and logic.

Art and Architecture: Stupas (Sanchi, Amaravati), rock-cut caves (Ajanta, Ellora), and Greco-Buddhist art (Gandhara) represent some of the finest achievements of Indian art. The Ajanta caves, with their exquisite murals, are a testament to the artistic and spiritual legacy of Buddhism.

Literature: Pali Canon, Jataka tales, and Mahayana sutras (Lotus Sutra) enriched literary traditions. The Jataka tales, which recount the Buddha’s previous lives, are not only religious texts but also valuable sources of folklore and moral instruction.

Jainism:

Literature: Jain texts in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit (Agamas) and contributions to Kannada, Tamil, and Gujarati literature. Jain scholars made significant contributions to grammar, logic, and mathematics, preserving and advancing knowledge during periods of political instability.

Architecture: Dilwara Temples (Mount Abu), Gomateshwara Statue (Shravanabelagola), and intricate manuscript illustrations. The Dilwara temples, with their exquisite marble carvings, are among the finest examples of Jain architecture.

Ethical Influence: Promotion of vegetarianism and animal welfare. Jainism’s emphasis on non-violence has had a lasting impact on Indian dietary practices and environmental ethics.

Relevance for UPSC

Ancient History: Understanding the socio-religious context of the 6th century BCE, including the role of Ganasanghas (republics) and urban centers, is crucial for answering questions on ancient Indian history.

Art and Culture: Contributions to India’s architectural heritage, pivotal for questions on UNESCO sites. The Ajanta and Ellora caves, Sanchi stupa, and Dilwara temples are frequently referenced in UPSC exams.

Philosophy: Concepts like Ahimsa and Anekantavada resonate in modern secularism and conflict resolution. These principles are relevant to contemporary debates on tolerance, pluralism, and non-violence.

Social Reforms: Both religions challenged caste discrimination, influencing later movements like Bhakti and Gandhi’s Satyagraha. Understanding their role in social reform is essential for questions on modern Indian history.

Current Affairs: Jainism’s recognition as a minority religion and Buddhism’s soft-power diplomacy in India’s foreign policy. The Indian government’s efforts to promote Buddhist tourism and cultural exchange are often highlighted in current affairs.

Conclusion

Buddhism and Jainism, though distinct, represent India’s pluralistic ethos and intellectual rigor. Their teachings on compassion, non-violence, and critical thinking remain globally relevant. For UPSC aspirants, mastering their historical trajectories, philosophical tenets, and cultural contributions is essential for answering questions on ancient history, ethics, and art. As living traditions, they continue to inspire movements for social justice and environmental sustainability, underscoring their timeless significance.

The study of Buddhism and Jainism not only provides insights into India’s spiritual heritage but also offers valuable lessons for addressing contemporary challenges. Their emphasis on ethical living, tolerance, and self-transformation serves as a reminder of the enduring power of spiritual wisdom in shaping a more just and compassionate world.