- UPSC LABS

- February 20, 2025

- 6:35 pm

- Ratings: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Coastal Landforms UPSC: Erosional and depositional

Coastal landforms are dynamic features shaped by the interplay of geological, marine, and atmospheric processes. They represent the interface between land and sea, constantly evolving due to erosional and depositional forces. Understanding these landforms is critical for geography, environmental science, and sustainable coastal management, particularly in countries like India with vast and densely populated coastlines. The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) emphasizes this topic due to its relevance to physical geography, ecology, and human-environment interactions.

Table of Contents

Erosional Coastal Landforms

Coastal erosion occurs when wave energy, tidal currents, and weathering processes dismantle rock and sediment. The rate of erosion depends on factors such as rock type, wave intensity, tidal range, and geological structure. Hard, resistant rocks like basalt erode slower than soft sedimentary rocks like limestone or clay.

Cliffs and Wave-Cut Platforms are quintessential erosional features. Cliffs form when waves attack the base of a coastal slope, creating a wave-cut notch. Over time, the overhang collapses, causing the cliff to retreat inland. Repeated collapses lead to a steep, vertical face. As cliffs retreat, they leave behind a gently sloping wave-cut platform, visible at low tide. The Konkan Coast in Maharashtra and the Varkala Cliffs in Kerala exemplify such formations in India.

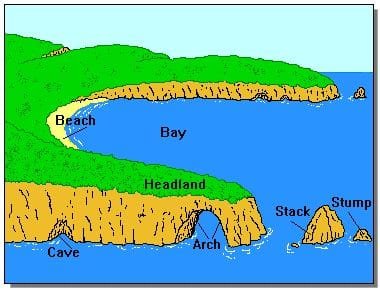

Headlands and Bays develop in areas of alternating rock resistance. Waves erode softer rocks faster, forming indented bays, while harder rocks persist as protruding headlands. The Malabar Coast showcases such differential erosion, with headlands like Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari) standing resilient against the Arabian Sea.

Caves, Arches, Stacks, and Stumps illustrate the lifecycle of erosional features. Waves exploit fractures in headlands, creating sea caves. Prolonged erosion merges caves from both sides, forming arches. Collapse of arches leaves isolated stacks, which further erode into stumps. The Neil Island in the Andamans and the Elephanta Caves near Mumbai demonstrate these stages.

Depositional Coastal Landforms

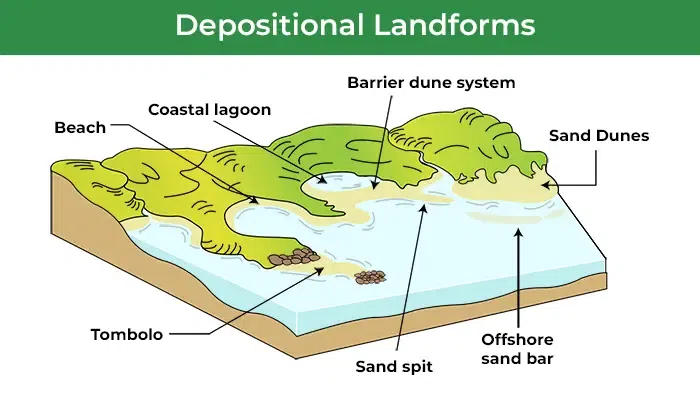

Depositional landforms arise when sediment transported by waves, currents, and rivers accumulates in low-energy environments. The balance between sediment supply and wave energy dictates their morphology.

Beaches are the most recognizable depositional features, composed of sand, gravel, or shell fragments. They form where wave energy diminishes, depositing sediments. Swash and backwash movements sort sediments, creating berms and ridges. Goa’s Anjuna Beach and Puri’s Golden Beach in Odisha are prime examples. Seasonal changes alter beach profiles, with winter storms often eroding them and summer waves rebuilding them.

Spits and Bars develop due to longshore drift, a process where waves transport sediment parallel to the coast. Spits are elongated ridges anchored to the mainland at one end, often curving landward at the tip. The Spurn Head in England is a classic spit, while India’s Muthupet Barrier in Tamil Nadu illustrates this phenomenon. Bars are submerged or exposed sediment ridges that span across bays, forming lagoon systems. The Chilika Lake in Odisha, Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon, was formed by such a bar.

Tombolos are rare depositional ridges connecting islands to the mainland. India’s Shivrajpur Beach in Gujarat is linked to a tombolo formation. Barrier Islands, like those along the Odisha coast, are long, narrow sandbanks parallel to the shore, protecting the mainland from storms.

Mudflats and Salt Marshes thrive in sheltered, low-energy zones like estuaries. Mudflats are exposed at low tide, composed of fine silt and organic matter. They transition into salt marshes when colonized by halophytic vegetation. The Sundarbans Delta, shared by India and Bangladesh, hosts extensive mudflats critical for biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

Mangroves are salt-tolerant trees stabilizing tropical and subtropical coastlines. Their dense root systems trap sediments, reducing erosion and buffering against cyclones. India’s Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, and the Bhitarkanika Mangroves in Odisha are UNESCO-protected sites, vital for coastal ecology and disaster resilience.

Factors Influencing Coastal Landform Development

Tectonic activity underpins regional coastal configurations. Emergent coasts, like parts of Tamil Nadu, are uplifted terraces with raised beaches, while submergent coasts, such as the Kerala backwaters, feature drowned valleys or rias. Sea-level changes, driven by glaciation or climate change, reshape coastlines over millennia. Current rates of sea-level rise (3–4 mm annually) threaten low-lying areas, including the Sundarbans and Lakshadweep.

Human Impact and Coastal Management

Human activities exacerbate coastal erosion and degradation. The construction of dams reduces sediment flow to deltas, while coastal infrastructure like seawalls disrupts natural processes. The 1991 Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification in India aims to balance development and conservation by restricting construction near shorelines. Community-led initiatives, such as mangrove afforestation in Tamil Nadu post-2004 tsunami, highlight the role of traditional knowledge in sustainable management.

Climate Change and Future Challenges

Rising sea levels and intensified storms under climate change threaten coastal habitats. Coral bleaching in the Gulf of Mannar and the Andamans weakens natural barriers, increasing erosion risks. Adaptive strategies, including the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Project, promote resilient infrastructure and ecosystem restoration.

Conclusion

Coastal landforms are archives of Earth’s dynamic processes, reflecting the ceaseless conflict between erosion and deposition. For UPSC aspirants, mastering this topic necessitates linking physical processes to real-world examples, policy frameworks, and sustainability challenges. India’s diverse coastline, from the rugged Western Ghats to the serene Sundarbans, offers a microcosm of global coastal phenomena, underscoring the urgency of interdisciplinary conservation efforts in the Anthropocene era.