- UPSC LABS

- February 25, 2025

- 6:35 pm

- Ratings: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Early Vedic Period UPSC

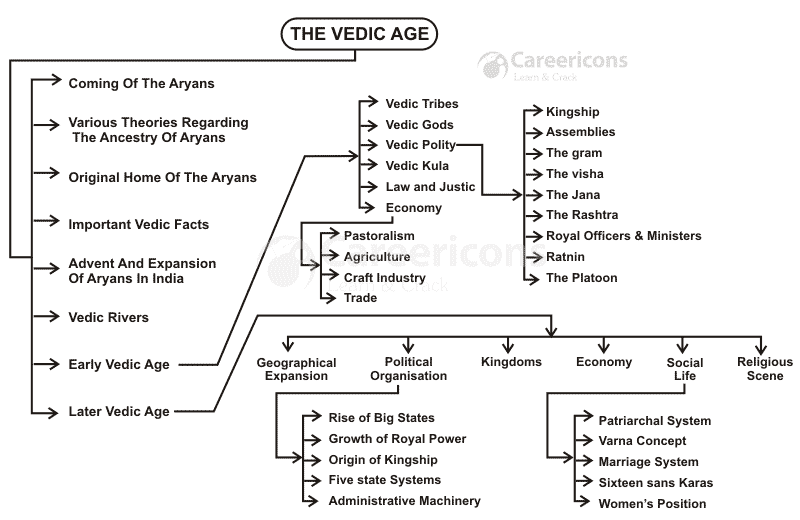

The Early Vedic Period, also called the Rigvedic Age (circa 1500–1000 BCE), marks the formative phase of Vedic civilization in the Indian subcontinent. This era is primarily reconstructed through the Rigveda, the oldest extant text in any Indo-European language, comprising 1,028 hymns divided into ten mandalas. The period is characterized by pastoral nomadism, tribal polity, and a pantheon of nature-centric deities. Understanding this epoch is crucial for UPSC aspirants as it lays the foundation for subsequent social, political, and religious developments in Indian history.

Table of Contents

Historical Context and Origin

The Rigvedic people, often identified as Indo-Aryans, migrated into the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent, likely from Central Asia. This migration is supported by linguistic and textual evidence, though debates persist between the Aryan Migration Theory (AMT) and the Indigenous Aryan Theory. The AMT posits a gradual influx of pastoral nomads through the Hindu Kush, while alternative theories argue for an indigenous origin. Recent genetic studies suggest a complex interplay of migrations and cultural exchanges, though the AMT remains widely accepted in academic circles.

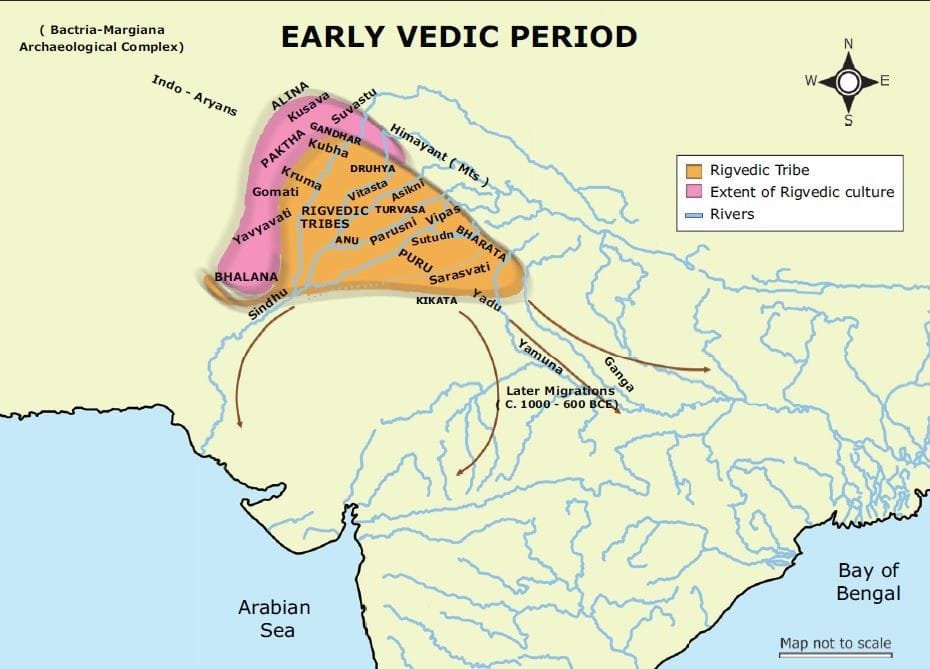

Geographically, the Rigvedic culture was centered in the Sapta Sindhu (Land of Seven Rivers), encompassing present-day Punjab, Haryana, and parts of northwestern India. Key rivers mentioned include the Sindhu (Indus), Saraswati (now extinct), Vitasta (Jhelum), and Parushni (Ravi). The Saraswati, revered as the “mother of rivers,” held sacred significance, indicating the ecological memory of a once-perennial river system.

Political Structure and Administration

The Rigvedic polity was tribal and egalitarian, organized around kin-based clans called janas. Each jana was governed by a hereditary chieftain (rajan), whose authority was neither absolute nor divine. The rajan’s primary duties included protecting the tribe, leading raids, and ensuring prosperity. Governance was participatory, with two assemblies—sabha (council of elders) and samiti (general assembly)—acting as checks on chiefly power. These bodies deliberated on matters of war, distribution of resources, and religious rituals, reflecting a proto-democratic ethos.

The military structure was rudimentary, with no standing army. During conflicts, the senani (army chief) mobilized tribesmen, who fought from chariots (ratha) drawn by horses. Warfare centered on cattle raids (gavishti), symbolizing both economic necessity and heroic valor. The Battle of the Ten Kings (Dasarajna), described in the seventh mandala, underscores the competitive yet fluid alliances among tribes, with the Bharata clan under King Sudas emerging victorious.

Social Organization

Rigvedic society was patriarchal and patrilineal, with the family (kula) as the basic unit. The grama (village) formed the nucleus of settlement, though urban centers were absent. Social stratification existed but was fluid, based on occupation rather than birth. The fourfold varna system—Brahmana (priests), Kshatriya (warriors), Vaishya (commoners), and Shudra (servants)—appears in the Purusha Sukta (10.90), though its application was likely symbolic, emphasizing cosmic order rather than rigid hierarchy.

Women enjoyed relative freedom compared to later periods. They participated in religious rituals, composed hymns (e.g., Lopamudra and Ghosha), and could choose spouses through swayamvara. The gotra system, regulating exogamous marriage alliances, began to take shape, reflecting early efforts to organize kinship ties.

Economic Life

The economy was predominantly pastoral, with cattle (gau) symbolizing wealth and prosperity. Terms like gomat (wealthy) and gavyuti (measure of distance) highlight their centrality. Agriculture, though secondary, involved barley (yava) cultivation using wooden ploughs. The absence of iron tools limited agrarian expansion; copper and bronze (ayas) were used for weapons and utensils.

Trade was limited and conducted through barter, with cattle serving as a medium of exchange. Craftsmanship included pottery, weaving, and chariot-making. The term pani denotes traders, often depicted as miserly in hymns, suggesting nascent economic disparities

Religion and Philosophy

Rigvedic religion was animistic and ritualistic, venerating natural forces deified as gods. Major deities included:

Indra: The warrior god of thunder and rain, invoked in nearly a quarter of the hymns.

Agni: The mediator between humans and gods, embodying sacrificial fire.

Varuna: The custodian of cosmic order (rta) and moral law.

Soma: Both a sacred hallucinogenic drink and a deity, central to rituals.

Rituals (yajnas) involved offerings of ghee, milk, and soma into the fire, accompanied by chants. Unlike later Hinduism, there were no temples or idol worship. The priestly class (Brahmins) gained prominence through their role in rituals, though their hegemony was not yet entrenched.

Philosophically, the Rigveda explores existential questions, such as the origin of the universe in the Nasadiya Sukta (10.129), which contemplates creation through a “cosmic heat” (tapas). The concept of rta (cosmic order) underpinned ethical and natural laws, later evolving into dharma.

Cultural and Intellectual Contributions

The Rigveda, composed in archaic Sanskrit, represents the zenith of oral literature. Its preservation through precise metrical recitation (shakhas) underscores the importance of memory in Vedic education. The guru-shishya tradition fostered intellectual rigor, with students memorizing hymns verbatim.

Poetic imagery in the Rigveda reflects a deep connection with nature, from the “luminous cows of dawn” to the “roaring rivers.” Hymns also encode historical data, such as the migration eastward and encounter with Indigenous communities (dasas or dasyus), depicted as dark-skinned and phallic-worshippers.

Archaeological and Textual Sources

Archaeological correlates of the Rigvedic culture are sparse, owing to their non-urban lifestyle. Sites like Bhagwanpura (Haryana) reveal overlapping Late Harappan and Painted Grey Ware (PGW) cultures, suggesting continuity and syncretism. Horse remains, pivotal to Vedic rituals, found in Swat Valley cemeteries, align with textual references.

The Rigveda remains the paramount source, supplemented by ancillary texts like the Brahmanas and Upanishads in later periods. Comparative linguistics and ethnobotanical studies (e.g., references to the Banyan tree) further validate the ecological setting described in the hymns.

Debates and Contemporary Relevance

Scholarly debates revolve around the Aryan identity and their relationship with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). While early historians posited a violent displacement of IVC by Aryans, recent evidence suggests a gradual assimilation. The absence of the horse in IVC contrasts with its Rigvedic prominence, yet genetic studies reveal a mingling of Steppe and Indus populations, complicating earlier narratives.

The Rigvedic emphasis on ecological harmony and participatory governance offers insights into contemporary issues like sustainable development and democratic decentralization. Its hymns, echoing universal human concerns, continue to influence Indian philosophy and arts.

Conclusion

The Early Vedic Period laid the bedrock for Indian civilization, shaping its socio-religious fabric. The transition to the Later Vedic Phase (1000–600 BCE) saw eastward expansion into the Gangetic plains, the crystallization of the caste system, and the emergence of monarchical states. Yet, the Rigvedic ethos of cosmic order (rta), communal participation, and spiritual inquiry endured, permeating subsequent epochs. For UPSC aspirants, grasping this period is essential to comprehend the continuity and transformation inherent in India’s historical trajectory, illustrating how ancient legacies inform modern identities.