- UPSC LABS

- February 25, 2025

- 6:35 pm

- Ratings: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

The Later Vedic Period UPSC

The Later Vedic period (c. 1000–600 BCE) represents a transformative era in ancient Indian history, marked by significant shifts in geography, socio-political structures, economy, religion, and philosophy. This period, succeeding the Early Vedic period (1500–1000 BCE) laid the groundwork for the evolution of classical Indian civilization. A thorough understanding of this phase is essential for UPSC aspirants, as it bridges the gap between the nomadic Vedic culture and the rise of urbanized Mahajanapadas. The period is illuminated by a rich corpus of texts, including the Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, Atharva Veda, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and the seminal Upanishads, collectively reflecting the dynamic changes of the time.

Table of Contents

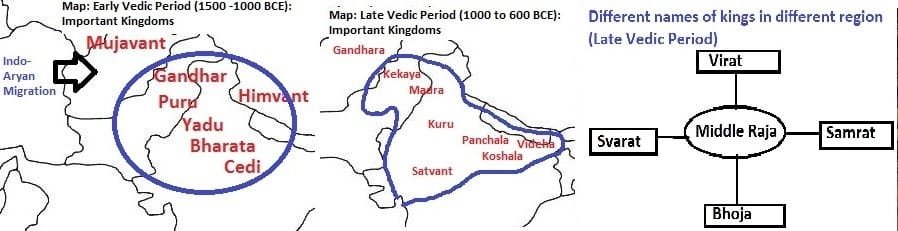

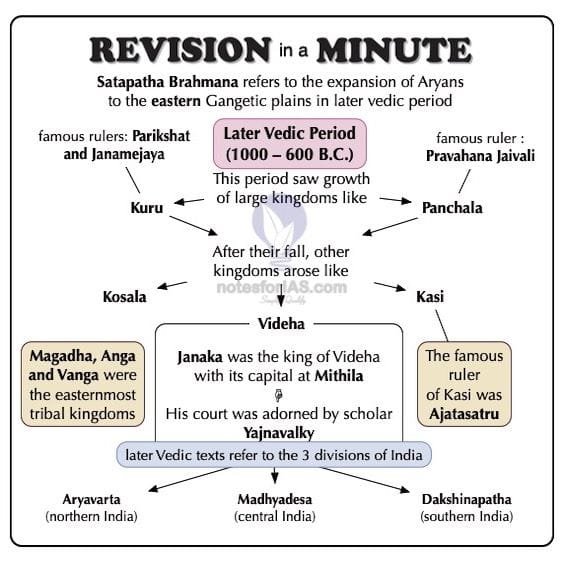

Geographical Expansion and Settlement Patterns

The Later Vedic period witnessed a decisive eastward shift of the Vedic people from the Sapta Sindhu (Indus region) to the Gangetic plains. This migration was driven by the need for fertile land to support an expanding agrarian economy. The Kuru and Panchala regions (modern-day Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh) emerged as pivotal centers, while settlements gradually spread to Kosala (eastern Uttar Pradesh), Videha (Bihar-Nepal border), and Magadha (south Bihar). The Ganga-Yamuna Doab became the heartland of Vedic culture, with rivers like the Ganges and Yamuna gaining sacred significance.

The shift to the Gangetic plains necessitated adaptations in settlement patterns. The use of iron tools, particularly the iron ploughshare, facilitated the clearance of dense forests and enhanced agricultural productivity. This period saw the rise of permanent villages (gramas) and the gradual transition from semi-nomadic pastoralism to settled farming. Crops such as rice, wheat, and barley became staples, supported by advanced irrigation techniques. The emphasis on land as a primary resource underscored the growing importance of territorial control, a theme that dominated subsequent political developments.

Political Organization and State Formation

The political landscape of the Later Vedic period evolved from tribal republics to more centralized monarchical systems. The tribal assemblies (Sabha and Samiti), which had shared power with the Rajan (chief) in the Early Vedic era, gradually diminished in influence. The Rajan transformed into a hereditary king, bolstered by elaborate rituals like the Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) and Rajasuya (royal consecration), which legitimized his divine authority. These ceremonies, administered by priests, emphasized the king’s role as the protector of his subjects and the upholder of Dharma (cosmic order).

The concept of Janapada (territorial state) began to take shape, with kingdoms like Kuru and Panchala emerging as prominent political entities. The administration became more structured, with officials such as the Senani (army chief), Purohita (priest), and Gramani (village headman) playing critical roles. Taxation systems evolved, with Bali (voluntary tribute) becoming a compulsory levy. By the end of this period, the stage was set for the rise of Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms), which would dominate the political landscape of the 6th century BCE.

Social Structure and Varna System

The Later Vedic society witnessed the crystallization of the varna system into a rigid hierarchical structure. The fourfold division of Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (farmers, traders), and Shudras (laborers) became more pronounced, with birth rather than occupation determining social status. The Brahmins and Kshatriyas occupied the top echelons, leveraging their roles in rituals and governance, respectively. The Vaishyas, though economically vital, faced increasing social marginalization, while the Shudras were relegated to menial tasks and excluded from Vedic rituals.

The patriarchal family (kula) became the primary social unit, with the Grihya Sutras codifying domestic rituals and duties. The gotra system, which regulated marriage alliances by prohibiting unions within the same lineage, gained prominence. Women, who enjoyed relative freedom in the Early Vedic period, saw their status decline. They were excluded from education and ritual participation, and practices like child marriage and sati (though not widespread) began to surface.

Economic Developments and Trade

The economy of the Later Vedic period transitioned from pastoralism to agriculture as the primary livelihood. Iron technology revolutionized farming, enabling large-scale cultivation and surplus production. Crops such as rice (in wet regions) and wheat (in drier areas) became central to the diet. The surplus generated facilitated trade and craft specialization. Artisans like carpenters, potters, and weavers organized into guilds (shrenis), fostering economic interdependence.

Trade, both local and long-distance, expanded significantly. The term Nishka referred to gold coins, indicating the emergence of a monetary economy. Rivers like the Ganges and Yamuna served as trade routes, linking regions from the northwest to Bengal. Commodities such as horses (imported from Central Asia), precious stones, and textiles were exchanged. Urban centers, though nascent, began to appear by the end of this period, heralding the second urbanization in India.

Religious Practices and Philosophical Evolution

Religion in the Later Vedic period became increasingly ritualistic, dominated by the Brahmins who orchestrated complex sacrifices (yajnas). The Brahmanas, texts explaining ritual procedures, emphasized the efficacy of mantras and ceremonies in maintaining cosmic order. Major sacrifices included the Ashvamedha, Rajasuya, and Vajapeya (chariot race ritual), which reinforced the king’s power and societal hierarchy.

However, this era also saw the germination of profound philosophical thought in the Upanishads, often called the Vedanta (end of the Vedas). These texts shifted focus from external rituals to internal meditation, exploring concepts like Brahman (universal soul), Atman (individual soul), karma (action), and moksha (liberation). The Brihadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanishads debated the nature of reality and the path to spiritual enlightenment, laying the foundation for Hindu philosophy.

Deities also evolved: Indra and Agni lost prominence, while Prajapati (creator god) and Vishnu (preserver) gained ascendancy. The Atharva Veda incorporated folk traditions, magic, and medicine, reflecting the synthesis of diverse cultural practices.

Literature and Educational Practices

The Later Vedic corpus expanded beyond the Rig Veda to include the Sama Veda (melodies), Yajur Veda (ritual formulas), and Atharva Veda (spells and charms). The Brahmanas, composed in prose, provided exegetical commentaries on rituals, while the Aranyakas (forest texts) and Upanishads marked a shift toward mystical and philosophical inquiry.

Education remained the preserve of the elite, transmitted orally in gurukulas (teacher’s households). Students memorized Vedic hymns and mastered rituals, with the Gayatri Mantra holding particular importance. The Upanishads encouraged intellectual debates, fostering a tradition of critical thinking that influenced later schools like Vedanta and Yoga.

Transition to the Mahajanapadas

By 600 BCE, the Later Vedic period gradually gave way to the Mahajanapada era, characterized by 16 major kingdoms and republics. Factors such as iron proliferation, agricultural surplus, and territorial conflicts fueled urbanization and state formation. Cities like Kaushambi and Rajagriha emerged as political and commercial hubs. This transition also saw the rise of heterodox movements, including Buddhism and Jainism, which challenged Vedic orthodoxy and caste rigidities.

Conclusion

The Later Vedic period was a pivotal epoch that reshaped India’s socio-cultural and political trajectory. The eastward expansion, agrarian economy, and stratified society laid the institutional foundations for classical Indian civilization. Philosophically, the Upanishadic quest for truth influenced diverse intellectual traditions, while politically, the rise of Janapadas set the stage for India’s first empires. For UPSC aspirants, grasping this period’s complexities is crucial to understanding the continuity and change that define India’s historical narrative. The interplay of geography, economy, religion, and statecraft during this era remains a testament to the dynamic evolution of ancient Indian society.