- UPSC LABS

- February 25, 2025

- 6:35 pm

- Ratings: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Mahajanapadas and the Rise of Republics

The period between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE in ancient India witnessed the emergence of Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms) and Gana Sanghas (republican states), marking a critical phase in the evolution of political, economic, and social structures. This era often termed the “Second Urbanization” in Indian history, laid the foundation for the rise of India’s first empires and the development of complex administrative systems. For UPSC aspirants, understanding this transformative period is essential, as it bridges the gap between the late Vedic age and the establishment of the Mauryan Empire. The sixteen Mahajanapadas, comprising both monarchies and republics, reflect the diversity of governance models in ancient India, while the Gana Sanghas exemplify early experiments in collective leadership and participatory governance.

Table of Contents

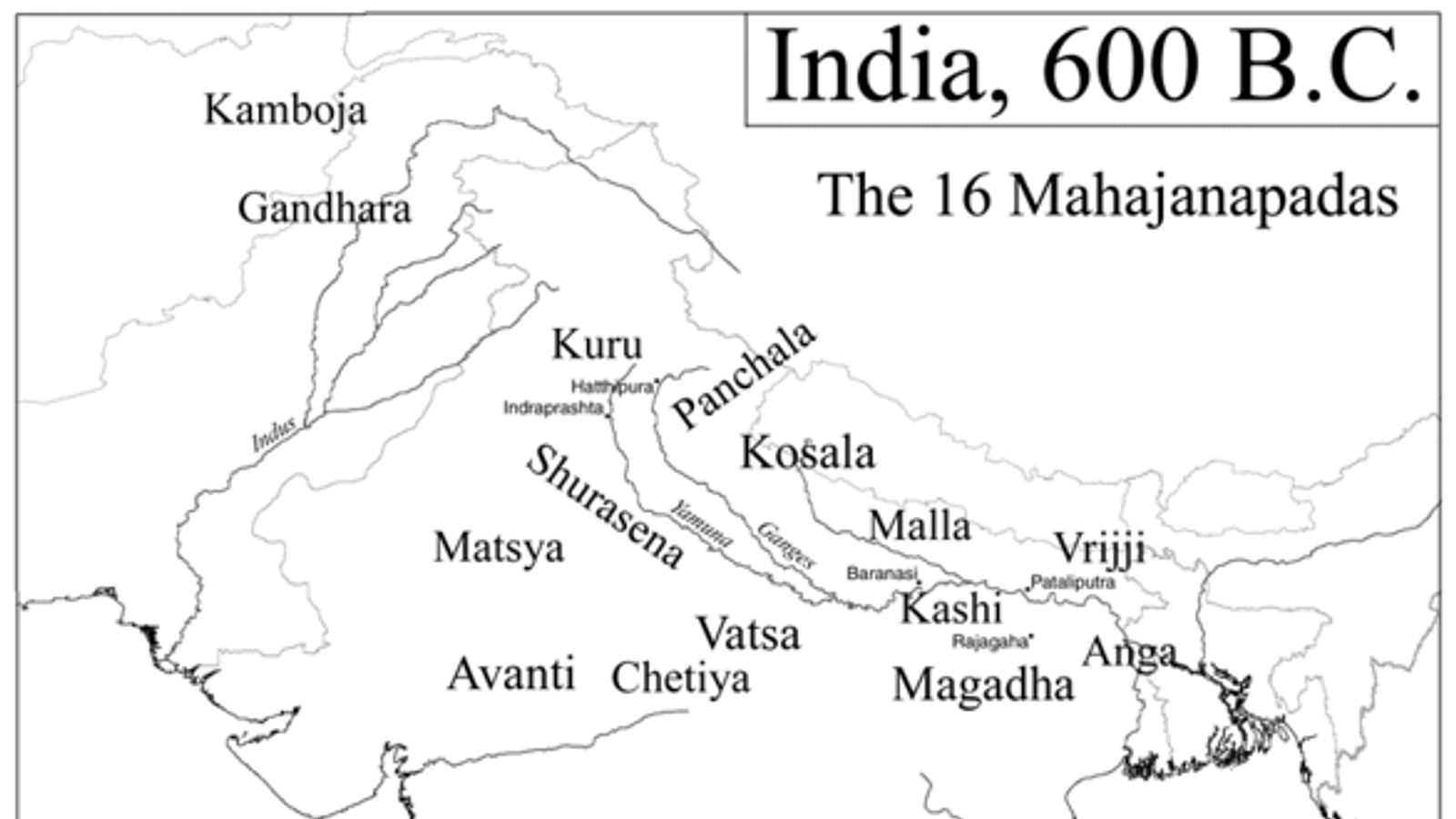

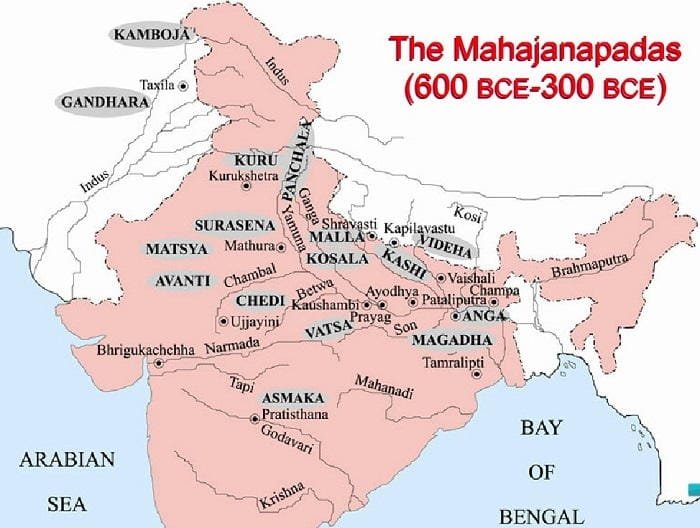

Historical Context and Sources

The term Mahajanapada (literally “great foothold of a tribe”) refers to territorial states that emerged after the decline of smaller tribal polities (Janapadas) of the Later Vedic period. By the 6th century BCE, the Indian subcontinent saw the consolidation of sixteen major Mahajanapadas, extending from Gandhara in the northwest to Anga in the east. The primary sources for studying this period include Buddhist texts like the Anguttara Nikaya and Mahavastu, Jain texts such as the Bhagavati Sutra, and later Sanskrit works like the Mahabharata and Puranas. Archaeological evidence, including Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), fortified cities, and early coinage (punch-marked coins), corroborates textual accounts of urbanization and economic growth.

The Sixteen Mahajanapadas

The sixteen Mahajanapadas were diverse in their geographical, political, and cultural attributes. Key monarchies included Magadha (modern Bihar), Kosala (Uttar Pradesh), Avanti (Malwa), and Vatsa (Allahabad region), while republics (Gana Sanghas) like the Vajji Confederacy (north Bihar) and Malla (Gorakhpur) were governed by collective assemblies. The Kuru and Panchala regions, once prominent in the Later Vedic period, transitioned into republics but were eventually overshadowed by powerful monarchies. Other notable Mahajanapadas included Gandhara (northwest Pakistan), Kamboja (Afghanistan), Chedi (Bundelkhand), and Matsya (Rajasthan).

Magadha emerged as the most influential monarchy due to its strategic location in the fertile Gangetic plains, rich iron deposits, and ambitious rulers like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru of the Haryanka dynasty. Kosala, ruled by King Prasenajit, and Avanti, under King Pradyota, were other prominent monarchies that engaged in frequent conflicts over territorial expansion.

1. Kashi

Kashi, centered around the modern city of Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, was one of the most prominent early Mahajanapadas. It was strategically located along the Ganges River, which facilitated trade and agriculture. Kashi was known for its wealth, cultural richness, and religious significance. The city of Varanasi (also called Benares) was a major hub for learning and spirituality.

Kashi frequently clashed with neighboring kingdoms like Kosala and Magadha. Initially, it was a powerful kingdom under King Brihadratha, but it was eventually annexed by Kosala during the reign of Prasenajit. Kashi’s decline marked the rise of Kosala and Magadha as dominant powers in the Gangetic plains.

2. Kosala

Kosala, located in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, was one of the most powerful Mahajanapadas. Its capital, Ayodhya, is renowned in Indian mythology as the birthplace of Lord Rama. Kosala also included important cities like Shravasti and Saketa.

Under King Prasenajit, Kosala expanded its territory by annexing Kashi and engaging in conflicts with Magadha. Kosala was known for its well-organized administration and prosperous economy, supported by fertile lands along the Sarayu River. However, internal strife and external pressures from Magadha led to its eventual decline.

3. Anga

Anga, located in present-day Bihar and West Bengal, was centered around its capital, Champa (modern Bhagalpur). Anga was a significant trading hub due to its proximity to the Ganges and its access to the Bay of Bengal.

Anga was often in conflict with its western neighbor, Magadha. Despite its economic prosperity, Anga was eventually conquered by Magadha under King Bimbisara, marking the beginning of Magadha’s rise to dominance.

4. Magadha

Magadha, located in southern Bihar, emerged as the most powerful Mahajanapada and laid the foundation for India’s first empires. Its early capitals were Rajagriha (Rajgir) and later Pataliputra (Patna). Magadha’s strategic location, fertile soil, and access to iron deposits in the Chota Nagpur Plateau contributed to its rise.

Under the Haryanka dynasty, rulers like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru expanded Magadha’s territory through conquests and alliances. The Nanda dynasty further consolidated its power, creating a vast empire that set the stage for the Mauryan Empire. Magadha’s military innovations, such as the use of war elephants and catapults, were instrumental in its success.

5. Vajji (Vrijji)

Vajji, also known as Vrijji, was a confederation of eight clans (including the Licchavis) located in northern Bihar. Its capital was Vaishali, a major center of trade and governance. The Vajji Confederacy was unique for its republican system of governance, where decisions were made collectively by elected representatives.

The Licchavis, the most prominent clan, were known for their democratic traditions and military prowess. However, internal divisions and external aggression from Magadha led to the confederation’s decline. The Battle of Vaishali (483 BCE) marked the end of Vajji’s independence.

6. Malla

The Mallas were a republican clan divided into two branches, with capitals at Kushinagar and Pava in modern-day Uttar Pradesh. Like the Vajji, the Mallas practiced a form of collective governance.

The Mallas were significant in the context of Buddhism, as Kushinagar is believed to be the place where Gautama Buddha attained Mahaparinirvana (final enlightenment). Despite their cultural importance, the Mallas were eventually absorbed by Magadha.

7. Chedi

Chedi, located in the Bundelkhand region of modern-day Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, was an important kingdom with its capital at Sotthivati (modern Banda). The Chedis are mentioned in the Mahabharata as allies of the Pandavas.

Chedi’s economy was based on agriculture and trade, with access to the Yamuna River. It maintained its independence for a long time but was eventually overshadowed by larger powers like Magadha.

8. Vatsa (Vamsa)

Vatsa, centered around its capital Kaushambi (near modern Allahabad), was a prosperous kingdom located along the Yamuna River. Kaushambi was a major trading and cultural center, with strong ties to Buddhism and Jainism.

Under King Udayana, Vatsa became a prominent power in the Gangetic plains. However, it faced constant pressure from Magadha and was eventually annexed.

9. Kuru

The Kuru kingdom, located in the Haryana and Delhi region, was one of the earliest political centers of ancient India. Its capital, Indraprastha, is mentioned in the Mahabharata.

The Kurus were initially a powerful tribe during the Later Vedic period but declined in importance by the 6th century BCE. They were eventually absorbed into larger kingdoms like Magadha.

10. Panchala

Panchala, located in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, was divided into northern and southern regions, with capitals at Ahichchhatra and Kampilya, respectively. The Panchalas were known for their cultural and religious contributions, particularly in the Vedic tradition.

Like the Kurus, the Panchalas declined in power and were absorbed by Magadha.

11. Matsya

Matsya, located in modern-day Rajasthan, was centered around its capital, Viratnagar (modern Bairat). The Matsyas are mentioned in the Mahabharata as allies of the Pandavas.

Matsya’s economy was based on agriculture and cattle rearing. It maintained its independence for a long time but was eventually overshadowed by larger powers.

12. Surasena

Surasena, located in the Mathura region of modern-day Uttar Pradesh, was an important kingdom with its capital at Mathura. The Yadavas, a prominent clan, ruled Surasena.

Mathura was a major center of trade and culture, with strong ties to Buddhism and Jainism. Surasena was eventually annexed by Magadha.

13. Assaka (Ashmaka)

Assaka, located in the Godavari River basin in modern-day Maharashtra, was the only Mahajanapada south of the Vindhya Range. Its capital was Potali or Pratishthana.

Assaka’s economy was based on agriculture and trade. It maintained its independence for a long time but was eventually absorbed into larger empires.

14. Avanti

Avanti, located in modern-day Madhya Pradesh, was divided into northern and southern regions, with capitals at Ujjain and Mahishmati, respectively. Avanti was a powerful kingdom with a strong military and prosperous economy.

Under King Pradyota, Avanti engaged in frequent conflicts with Magadha. However, it was eventually annexed by Magadha under the Shishunaga dynasty.

15. Gandhara

Gandhara, located in modern-day northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, was a major center of trade and culture. Its capital, Taxila, was a renowned hub of learning.

Gandhara’s strategic location made it a crossroads of cultures, with influences from Persia, Greece, and Central Asia. It was eventually annexed by the Achaemenid Empire and later by Alexander the Great.

16. Kamboja

Kamboja, located in modern-day Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan, was known for its skilled horsemen and warriors. It was a significant center of trade and culture.

Kamboja’s strategic location made it a target for foreign invasions. It was eventually absorbed into larger empires like the Mauryan Empire.

Political Structures: Monarchies vs. Republic

The Mahajanapadas were broadly divided into monarchical states and republican states (Gana Sanghas). Monarchies were characterized by centralized authority, hereditary kingship, and a hierarchical bureaucracy. Kingship was legitimized through Vedic rituals like the Rajasuya (royal consecration) and military conquests. In contrast, republics operated through collective decision-making bodies, such as assemblies of elected representatives (rajas) or tribal oligarchies. The Vajji Confederacy, a coalition of eight clans including the Licchavis, and the Mallas were among the most renowned republics.

Republican governance emphasized consensus-building and egalitarian principles, though power often remained concentrated among elite clans. The Licchavis of Vaishali, for instance, were governed by a General Assembly (Parishad) comprising 7,707 members, representing various kinship groups. Decisions on war, treaties, and resource allocation were made through debates and voting. Despite their participatory nature, republics faced challenges in maintaining unity against external threats, particularly from expansionist monarchies like Magadha.

Formation of the Republics (Gana Sanghas)

The rise of Gana Sanghas can be traced to the socio-political changes in the Later Vedic period. The decline of tribal egalitarianism and the need for larger political entities to manage resources and conflicts led to the formation of republics. Iron technology played a pivotal role by enabling agricultural surplus, which supported non-agrarian classes like artisans, traders, and warriors. The Vajji and Malla republics, located in the fertile Gangetic plains, thrived on rice cultivation and trade along river routes.

Republics often emerged from kshatriya clans that rejected monarchical centralization. For instance, the Shakyas (the clan of Gautama Buddha) and the Koliyas were republican tribes in the Himalayan foothills. These clans retained their autonomy through collective governance and military cooperation. The Bhagavati Sutra lists 363 republican states, though only a few, like Vajji and Malla, held significant power.

Administrative Systems of the Republics

The Gana Sanghas operated through a complex system of assemblies and elected officials. Key features included:

Assembly Governance: Major decisions were made in assemblies comprising male members of the ruling clans. The Licchavi Parishad required a quorum and followed strict procedural rules.

Elected Representatives: Leaders (Mukhyas) were elected for fixed terms and held accountable for their actions.

Judicial Mechanisms: Disputes were resolved through councils, with penalties ranging from fines to expulsion.

Military Organization: Republics maintained militias composed of citizen-soldiers, contrasting with the professional armies of monarchies.

However, the republican system was exclusionary, as women, shudras, and non-clan members were barred from participation.

Economic and Social Factors

The Mahajanapada period saw significant economic growth driven by iron-based agriculture, trade networks, and urbanization. The Gangetic plains became the agricultural heartland, with rice cultivation supporting dense populations. Surplus production facilitated the rise of urban centers like Rajagriha (Magadha’s capital), Vaishali (Vajji’s capital), and Kaushambi (Vatsa’s capital).

Trade expanded along routes such as the Uttarapatha (northern route) linking Taxila to Pataliputra and the Dakshinapatha (southern route) connecting Magadha to Deccan. Punch-marked coins, issued by merchants and guilds, standardized transactions, while guilds (shrenis) regulated crafts like pottery, weaving, and metallurgy.

Socially, the varna system became more rigid, but the rise of merchant classes (vaishyas) and ascetic traditions (Buddhism, Jainism) challenged Brahmanical dominance. The Gana Sanghas, often aligned with non-Vedic traditions, promoted social mobility for wealthy traders and landowners.

Military Conflicts and the Rise of Magadha

The 6th century BCE was marked by incessant warfare among the Mahajanapadas for territorial control. Magadha’s ascendancy began under Bimbisara (544–492 BCE), who employed matrimonial alliances, diplomacy, and military innovation. His marriage to Kosala Devi (sister of Prasenajit) secured strategic alliances, while his conquest of Anga provided access to the Ganges delta’s resources.

Ajatashatru (492–460 BCE), Bimbisara’s son, further expanded Magadha through wars with Kosala and Vajji. The Battle of Vaishali (483 BCE) against the Licchavis lasted 16 years and showcased Magadha’s use of war elephants and catapults. By the 4th century BCE, the Nanda dynasty consolidated Magadha’s power, creating the largest empire in India prior to the Mauryas.

Decline of the Republics

The republican states gradually declined due to internal fragmentation and external aggression. The Vajji Confederacy collapsed after Ajatashatru sowed discord among its clans, while the Mallas were absorbed by Magadha. Monarchies, with their centralized armies and administrative efficiency, proved more adaptable to large-scale warfare and resource management. The Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE) later eradicated the remaining republics, replacing participatory governance with imperial bureaucracy.

Legacy and Significance for UPSC

The Mahajanapadas and Gana Sanghas represent a foundational phase in India’s political evolution. The republics, though short-lived, introduced concepts of collective governance and accountability, influencing later democratic traditions. Monarchies like Magadha demonstrated the efficacy of centralized administration, setting precedents for the Mauryan and Gupta empires.

For UPSC aspirants, this period underscores themes like state formation, economic integration, and socio-religious movements. The interplay between republics and monarchies highlights the diversity of ancient Indian polity, while the rise of Magadha illustrates the role of geography, technology, and leadership in historical change. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for analyzing subsequent developments in Indian history, from the Mauryan Empire to the emergence of classical Hinduism and Buddhism.

Conclusion

The Mahajanapadas and Gana Sanghas era was a crucible of political experimentation and socio-economic transformation. The republics, with their emphasis on participatory governance, and the monarchies, with their centralized power, together shaped the trajectory of ancient Indian civilization. For UPSC candidates, mastering this period provides critical insights into the complexities of early statecraft, the roots of India’s urban and philosophical heritage, and the enduring legacy of its ancient political innovations.